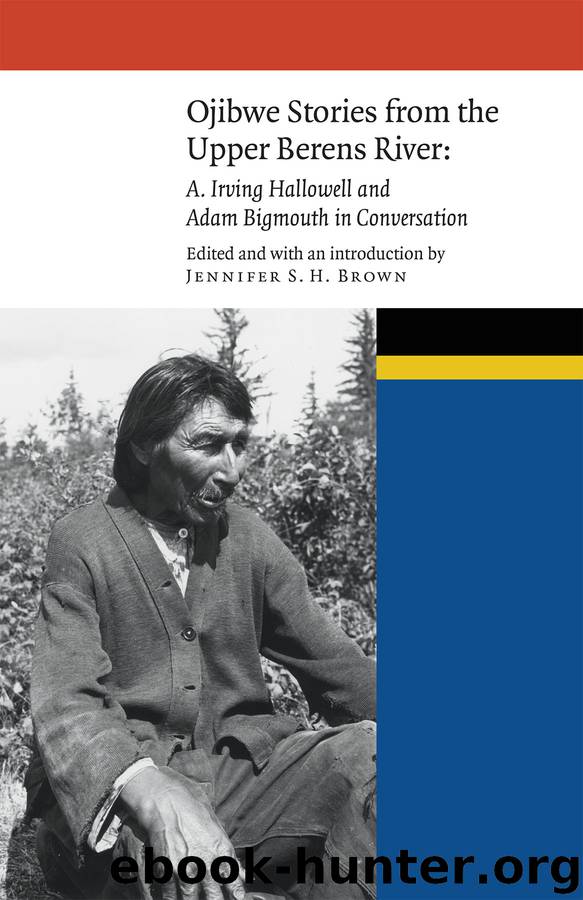

Ojibwe Stories of the Upper Berens River by Jennifer S. H. Brown

Author:Jennifer S. H. Brown [Brown, Jennifer S. H.]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: SOC021000 Social Science / Ethnic Studies / Native American Studies

ISBN: 9781496202253

Publisher: University of Nebraska Press

Published: 2017-10-25T06:00:00+00:00

The following paragraphs draw in part on a paper that Maureen Matthews and I presented to the American Society for Ethnohistory in November 1995, building on our Berens River researches and extended conversations with Margaret Simmons and Ojibwe linguist Roger Roulette, as well as on Hallowell’s papers.

Item 1: When William Berens told Hallowell that women got blamed for everything, he had in mind the many ways that women could frustrate or endanger male activities, livelihood, and even health. When Adam and other young males fasted to establish ties with dreamed visitors, they had to avoid their sisters and other females before fasting, or the pawaganak would not come to them. Hallowell found: “From all accounts, the older Indians were very strict about this,” such that male sexual activity before fasting was probably kept to a minimum (2010, 332). Speaking more generally, Adam said men who “bothered the women” at a young age would not be strong and healthy (see “HBC Manager in Trouble,” pt. 2). Older people told Hallowell that “a man would have more mental power if he kept away from women and did not marry”; he could conserve his power and not waste it. Similarly, women were not to step over men’s legs or possessions; to do so would make the men weak and poor runners.

The core issue for men had to do with women’s “uncleanness,” related to their menses. Hallowell’s notes recorded the term winewisiwin [wiiniziwin, uncleanliness] for catamenia, or as Baraga’s dictionary translated it, “monthly flowings,” which men saw as both threatening and repulsive. (One man described them to Hallowell as “slime between the legs.”) The root verb is wiinizi, “being dirty or impure”; in contrast, bekize is the state of “being clean or pure”—or “religious purity,” as Hallowell glossed it. The Cree employed the parallel concept pikisiw, “someone is clean,” in speaking of the condition that a male needed to be in on a dream quest (Brightman 1993, 79). Fasting in the bush occurred in a clean place, away from women, dogs, and other sources of pollution. Wild animals were also “clean,” and their “bosses” (manidoons, diminutive spirits) were offended and kept them away from hunters if a menstruating or pregnant woman came near. Also, such women were not to lift fishnets, tend snares or traps, or have contact with animal remains; their actions and condition could threaten both food security and male hunters’ livelihood and powers. More profoundly, they put at risk men’s abilities to call spirits into the shaking tent, to heal people through the sweat lodge, and to conduct Midewiwin or Waabano ceremonies. Menstruating women did not take part in ceremonies because they would “put them into disorder,” as Roulette put it (Brown and Matthews 1995). Berens River Ojibwe women held no ceremonial roles except occasionally after menopause when, as Hallowell was told, “they are considered to be more like men.” The medicine woman in “Midewiwin Miracles” (pt. 5) was postmenopausal. Yet William Berens and Adam Bigmouth both acknowledged that some women had powers to counter sorcery or even to kill windigos (see “Windigos Killed by Two Women,” pt.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(15357)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14508)

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(12393)

Underground: A Human History of the Worlds Beneath Our Feet by Will Hunt(12099)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12028)

Wiseguy by Nicholas Pileggi(5786)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5446)

Perfect Rhythm by Jae(5404)

American History Stories, Volume III (Yesterday's Classics) by Pratt Mara L(5308)

Paper Towns by Green John(5191)

Pale Blue Dot by Carl Sagan(5008)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4964)

The Mayflower and the Pilgrims' New World by Nathaniel Philbrick(4504)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4490)

Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI by David Grann(4447)

The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen(4390)

Too Much and Not the Mood by Durga Chew-Bose(4348)

The Borden Murders by Sarah Miller(4325)

Sticky Fingers by Joe Hagan(4199)